Headline:

Smart Energy Systems and the Decarbonisation of the Energy Sector – Workshop Explores Pressing Questions

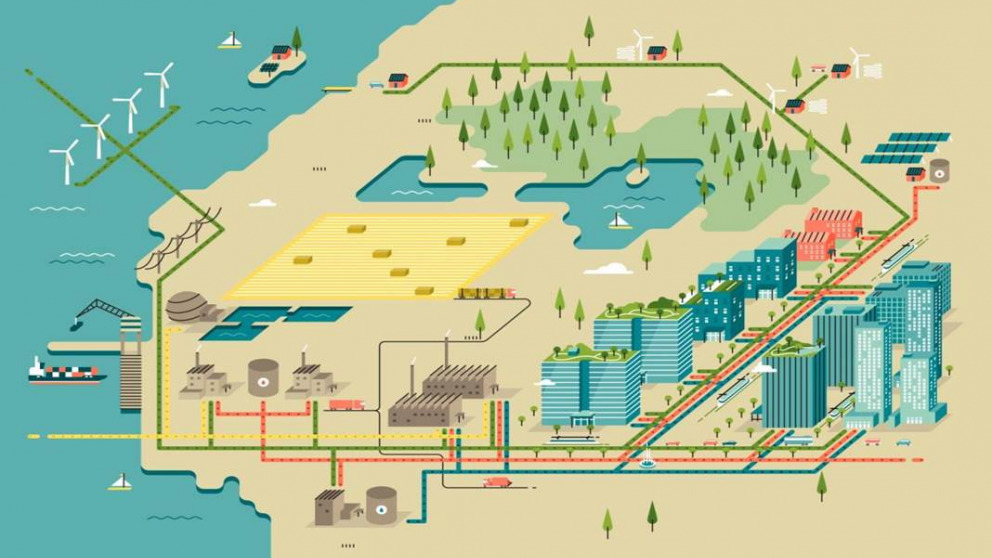

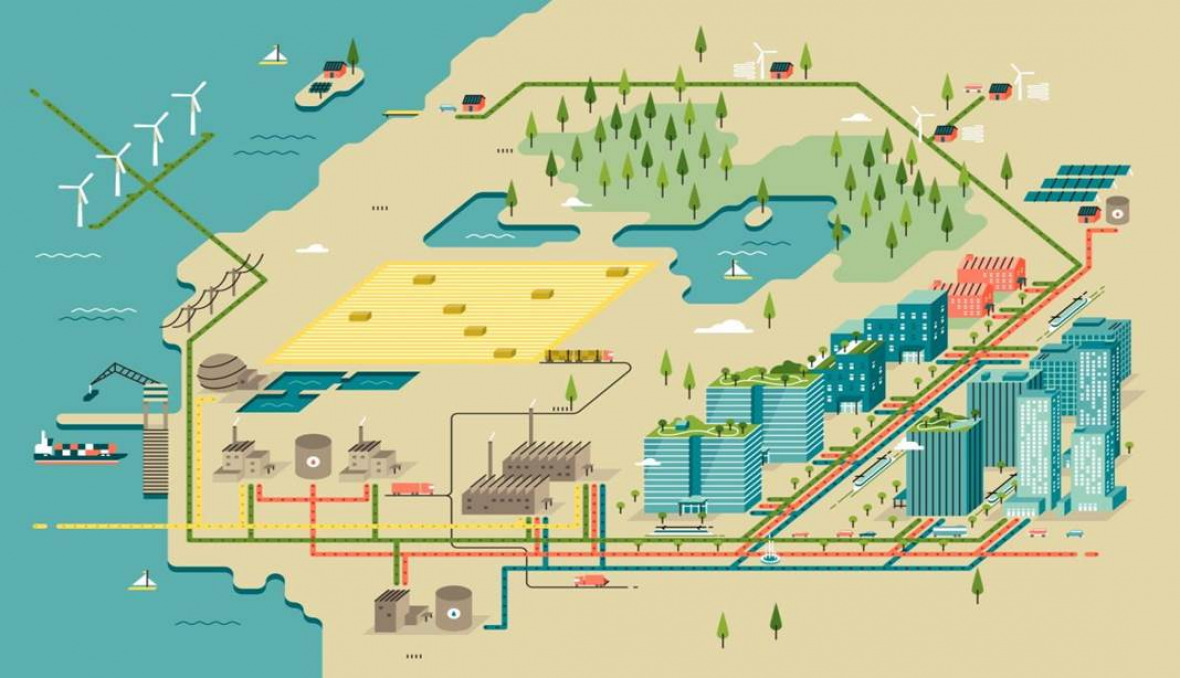

What are ‘smart energy systems’ and how could they help to make the energy sector more efficient and more sustainable? With the growing share of renewable energy sources, there is an increasing need for the enhanced flexibility of so-called ‘smart’ systems to facilitate their integration with electricity infrastructure and to connect the power sector with heating and transportation. This is particularly true for cities, where energy infrastructures are situated in close proximity. At a workshop held at the IASS on 24–25 February 2016, experts from research, utilities, industry and academia gathered to discuss concepts, technologies, and pilot projects for smart energy systems.

The central theme of discussions was the challenge of implementing an integrated approach that includes all possible energy vectors within its scope and maximizes synergies in order to enable a reliable and 100% renewable-based energy system. Discussions revealed that the very process of developing energy systems must be evaluated and adjusted in light of a number of pressing questions: What is the optimum we are seeking when developing a sustainable and smart energy system? What are people’s needs, and how can we meet them while creating systems that are cost effective?

A smart energy system is not just about electricity

Henrik Lund of Aalborg University (Denmark) emphasised that in order to achieve an entirely sustainable energy supply, we must expand the scope of our focus beyond electricity generation from renewables. The latter should be seen as part of a smart energy system that includes heating, industry, gas and transportation, and which opens the way to cheaper and better solutions. Energy storage solutions for thermal, gas, and liquid fuel options are far more affordable than electricity storage, making the latter the least realistic solution for the integration of wind energy, to name just one example.

In this perspective, smart district heating and cooling concepts for cities can have a major impact on reducing fossil-based energy generation. This was also stressed by Anders Dyrelund from Rambøll Energy, who has been instrumental in the development of Denmark’s National Heat Plan. Denmark was able to reduce its oil consumption in the heating sector by more than 90% between 1972 and 2009, though the specificities of the Danish energy system limit the possibilities of adapting it to other countries.

Coupling of energy sectors must be intensified

The workshop participants agreed that the coupling of all energy sectors must be intensified. In this respect, heat pumps represent a key technology to achieving a drastically reduced carbon footprint by using electric energy from renewables for heating. David Pearson from Star Renewable Energy presented a highly efficient heat pump project implemented in Drammen, Norway that supplies the district’s heating system, providing 60 000 residents and businesses with heat using water drawn from the icy depths of a nearby fjord to heat water in the system to 90 °C. Seventy-five percent of the system’s 14 MW heating output is generated using a clean and local source of energy – in this case seawater with a temperature of 8–10 °C. The adoption of power-to-gas applications – another promising sector-coupling technology in which electrical power is converted to a gas fuel – has stalled in the face of the considerable investments that its implementation requires and only a few prototypes exist in Europe, most in Germany. According to Harald Lange from Siemens, this technology is not economically viable in the energy system at present, but this could change if it was connected to the transport sector.

The role of combined heat and power plants (CHP) was discussed by Juan Villeda from General Electric, who presented a new hybrid power plant concept developed by the company as it adapts its portfolio to the changing energy system and the increasing decentralisation of energy generation. The system comprises a CHP combining a small-scale gas turbine with photovoltaics, an innovative battery solution and thermal energy storage capacity. The plant provides most of the energy for GE’s production facility in Berlin Marienfelde and represents a significant departure from centralised power generation solutions. CHP can be seen as a bridge technology to reduce GHG emissions in the short term and also helps to relieve power grid congestion. But, as some participants noted, ultimately we must abandon fossil fuels.

Smart and sustainable cities – havens for the affluent?

Bryan Hannegan from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), who served as a senior energy advisor to President George W. Bush, offered insights into the Energy Systems Integration (ESI) programme of the US Department of Energy. This programme aims to lead the way in overhauling US electricity infrastructure. Hannegan stressed that cooperation among different stakeholders is the key to reaching a reliable, effective, and economically feasible integration of renewable energy into the electric grid. He also highlighted the need to cooperate on an international level to maximize synergy effects and the returns that can be achieved by sharing knowledge and best practice experiences.

Concepts for sustainable cities were presented by Gerhard Stryi-Hipp, with the example of Frankfurt Main, and by Jiancheng Yu from the Tianjin Electric Power Company, who presented the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-city project. Galina Churkina from IASS highlighted the potential equity issues that these smart and sustainable cities will face as they are unlikely to be affordable for most people. At present, however, few experiences are available for study and most sustainable cities are still in the planning and development phases.

Good communication is crucial for social acceptance

As discussions at the workshop showed, smart energy systems can be variously defined, ranging from flexible response management and the anticipation of future developments to systems which prioritise resource efficiency, synergies, and the minimization of environmental impacts. What these systems share, the participants emphasised, is their ability to deliver reductions in greenhouse gas emissions. It is this attribute which will potentially make them a crucial instrument in efforts to secure universal access to energy. It was stressed in discussions however that smart energy solutions require working business models if they are to become a reality. The spectre of stranded assets – failed investments in technologies and concepts that result in a loss of value for investors and which may present obstacles to future investments in 10 or 20 years – was also discussed at the workshop. Efforts to heighten social acceptance of smart energy systems, the participants agreed, should focus on raising choice awareness and ensuring that the availability of concrete alternatives is effectively communicated to consumers and policymakers. A central finding of the workshop was the need for further research to develop a model of stakeholder management that creates feed-back loops connecting policymakers with all other stakeholders.